Want to get ahead? Fail more (But do it like this)

The Hidden Power of Failure: A Quiet Expert's Greatest Teacher

The paradox of hidden learning

Success stories fill our LinkedIn feeds, conference stages, and industry magazines. Yet the most profound learning - the kind that transforms good professionals into true experts - happens in the shadows of failure. This presents a peculiar paradox: the very experiences that accelerate expertise development are the ones we're least comfortable discussing.

Last week, I shared why failure inspired me to start The Quiet Expert series - how my own startup's collapse became the catalyst for a deeper understanding of expertise development. Today, I want to shift from the personal "why" to the practical "how": specifically, how to transform failure from a source of shame into a foundation for authentic expertise and meaningful professional relationships.

For quiet experts particularly, this transformation is crucial. We don't typically build our reputations through charismatic storytelling or bold self-promotion. Instead, our credibility comes from demonstrated competence and thoughtful reflection. Failure, when properly processed and communicated, becomes one of our most powerful tools for both learning and connection.

The failure stigma: Why we hide our greatest teachers

The reluctance to discuss failure runs deeper than mere embarrassment. Our professional cultures, especially in technical and operational roles, are built on the premise of getting things right the first time. Consider the surgeon who cannot afford to "learn by doing" with patient lives at stake, or the software engineer whose failed deployment could cost millions in downtime.

This perfectionist culture creates what psychologist Carol Dweck calls a "fixed mindset" environment—one where abilities are seen as static traits rather than skills that develop through challenge and failure. The result is professionals who become increasingly risk-averse as they advance, paradoxically limiting their growth just when they have the experience to tackle more complex problems.

But there's a hidden cost to this failure-avoidance: innovation stagnation. James Dyson created 5,126 failed prototypes before perfecting his revolutionary vacuum design. Each "failure" provided data that success alone never could. The key insight isn't that failure is good - it's that the right kind of failure, properly analyzed, accelerates expertise development in ways that success cannot replicate.

Reframing failure as high-quality data

Not all failures are created equal. There's a crucial distinction between "low-quality failure" - mistakes born from carelessness or lack of preparation - and "high-quality failure" that emerges from pushing beyond current capabilities in pursuit of ambitious goals.

High-quality failure has three characteristics:

Intelligent risk-taking: The failure resulted from attempting something worthwhile that pushed beyond comfort zones. When Netflix decided to split its DVD and streaming services into separate brands (Qwikster), the backlash was swift and severe. But this "failure" provided crucial market feedback that informed their successful pivot to streaming-first content creation.

Clear learning objectives: The attempt was structured to generate useful data regardless of outcome. Pharmaceutical companies don't view failed drug trials as defeats—they're structured experiments that eliminate possibilities and inform future research directions.

Systematic reflection: The failure is analyzed methodically to extract transferable insights rather than dismissed as bad luck or poor timing.

This reframing transforms failure from a source of shame into what it actually is: premium data that successful experiences simply cannot provide. It's expensive data - costly in time, resources, and sometimes reputation - but it's also uniquely valuable because it reveals the boundaries of what works and why.

The Failure Portfolio: Systematic learning from setbacks

Just as investment portfolios require diversification and regular review, your failure experiences need systematic documentation and analysis. This isn't about dwelling on mistakes, but about building a personal database of hard-won insights.

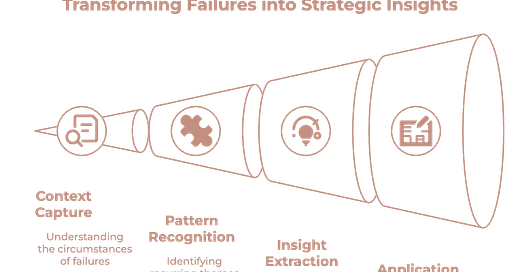

The framework I've developed includes four components:

Communicating about failure: Building credibility through vulnerability

The most transformative aspect of failure literacy is the ability to discuss failure in ways that enhance rather than diminish professional credibility. This requires a delicate balance between honest reflection and strategic communication.

Lead with learning, not drama: Sara Blakely, founder of Spanx, was rejected by manufacturer after manufacturer before finding one willing to produce her product. But rather than focussing on the rejections, she systematically documented each rejection, noting specific objections and concerns that later informed her business strategy. The failure becomes influential rather than a liability.

Be specific about insights: Vague statements like "I learned a lot from that experience" add little value. Instead, articulate specific, transferable insights: "I learned that stakeholder alignment is more fragile than I assumed, especially when individual incentives aren't clearly aligned with collective goals."

Connect to current value: Show how past failures directly inform current judgment and decision-making. This isn't about dwelling on mistakes, but demonstrating how those experiences contribute to present competence.

The goal isn't confession or self-deprecation - it's establishing expertise through demonstrated learning ability. When you can discuss failure thoughtfully, you signal to others that you're someone who learns from experience rather than repeating mistakes.

Creating failure-positive environments

For quiet experts who often find themselves in leadership or mentoring roles, creating environments where others can fail safely becomes a crucial skill. This isn't about accepting mediocrity or excusing poor performance - it's about distinguishing between failures that indicate lack of care and failures that indicate ambitious attempts.

Psychological Safety Framework: Google's Project Aristotle identified psychological safety as the key factor in high-performing teams. This doesn't mean eliminating accountability, but rather creating conditions where people can take intelligent risks without fear of punishment for outcomes beyond their control.

Productive Failure Design: In learning environments, some failures can be intentionally designed to maximize insight generation while minimizing real-world consequences. This might involve pilot programs, controlled experiments, or simulation exercises that allow people to experience failure's teaching power without catastrophic consequences.

Failure Retrospectives: Just as successful projects deserve post-mortems, significant failures deserve structured analysis sessions. The goal isn't blame assignment but insight extraction and system improvement.

At one of the start-ups I worked for, we had a value “Make New Mistakes”. The aim was not to foster an environment where mistakes were OK, but to create a safe environment where everyone felt empowered to try something different. If it failed, that was OK - you shared your learnings and you tried again with a different approach. It was one of the quickest-moving companies I ever worked for, because of this relentless attitude to normalising and safeguarding failure.

cred: Vita Mojo - https://careers.vitamojo.com/

The Quiet Expert's failure advantage

Quiet experts possess unique advantages in learning from failure. Our tendency toward reflection rather than immediate reaction means we're more likely to extract meaningful insights from difficult experiences. Our preference for depth over breadth means we're more willing to sit with complexity rather than rushing to simple explanations.

Perhaps most importantly, our authenticity in discussing failure can create deeper professional relationships than success stories ever could. When you can share genuine insights from genuine mistakes, you invite others into real learning conversations rather than surface-level networking.

This failure literacy accelerates expertise development in ways that success alone cannot match. It builds resilience, develops judgment, and creates the kind of hard-won wisdom that distinguishes true experts from merely competent professionals.

Conclusion: Failure as a credential

The ability to fail well - to extract maximum learning from minimum setbacks, to communicate about failure in ways that enhance credibility, and to create environments where others can fail safely - isn't just a nice-to-have skill. For quiet experts, it's often the differentiator between good and exceptional.

Your failures, properly processed and thoughtfully shared, become credentials that no success story can replicate. They demonstrate not just what you know, but how you learn, how you adapt, and how you think under pressure.

The quiet expert's path to influence doesn't run through perfect execution - it runs through demonstrated learning ability. And nothing demonstrates learning ability quite like the thoughtful discussion of intelligent failure.

In our next article, we'll explore how to identify and develop your unique expertise signature - the distinctive combination of skills, perspectives, and insights that only you can bring to your field. Because while failure teaches us how to learn, expertise teaches us what to learn and why it matters.